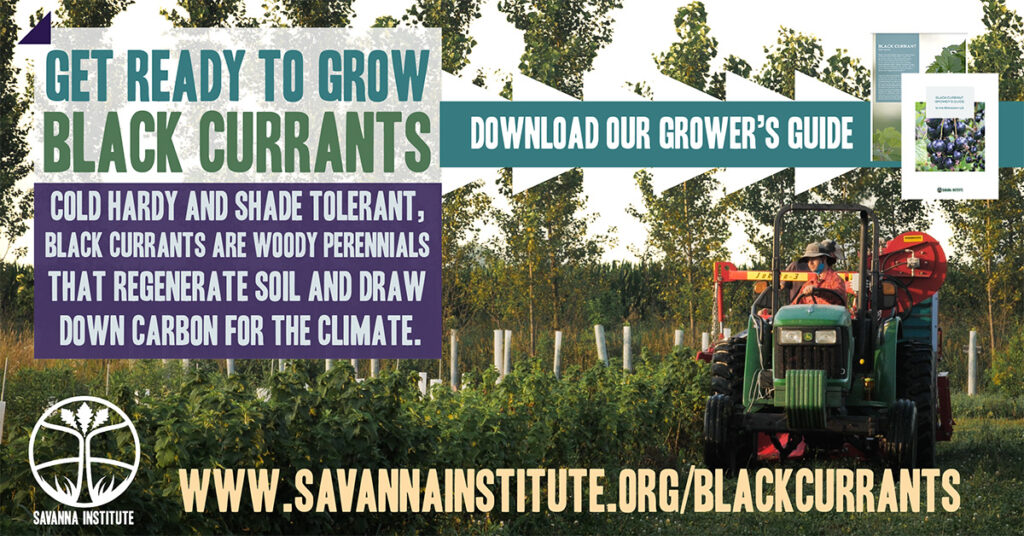

Kevin Wolz: Here in the US, around the year 1900, the black currant industry was about as large as the blackberry industry is today. Blackberries are not the most common fruit, but everyone knows what a blackberry is, and you can buy them in basically any store. And that’s what black currants were like at around the turn of the century in 1900.

Agroforestry researcher and black currant grower Kevin Wolz describes the fraught history of black currants and white pine blister rust for a recent on-farm educational video about this perennial fruit.

What happened was, around 1920 or in the teens, this disease showed up in the US called white pine blister rust. And it’s not a disease of currants, but it’s a disease of the white pine tree. And at the time, that tree was the main tree for the timber industry in the eastern US. And so the government got a little frantic because the timber industry was like, ‘Hey, we have no idea what’s going on here. We need your help.’ And so they sicced all the scientists on it, and took them a while, but then they figured out that this white pine blister rust – which is completely lethal to white pine trees – doesn’t actually go from white pine to white pine. It actually has to go through an intermediary host. So it goes from white pine to black currant or gooseberry or anything in the Ribes genus back to white pine. So if you remove this intermediate host, you break the cycle and you get rid of the disease.

So the solution to that was that the government spent a lot of money, and they paid the Civilian Conservation Corps and local groups and farmers to basically eradicate Ribes from North America. They had a federal ban on growing currants and gooseberries in the US, and they also sent crews around and burned to the ground these farms and understories of woods to get rid of as much Ribes as they could.

So once that federal ban was in place, that lasted all the way until the fifties, when in Canada they finally bred the first white pine blister rust resistant cultivars. And so now all the cultivars we use to this day are descendants of those original cultivars and are resistant or immune to that disease. So it’s kind of a moot point now. And the federal ban was lifted at that point. But still, some states in the Northeast have statewide bans on growing blackcurrants that are just relics of this time and they haven’t changed it. And so the problem is that even though it’s been legal again to grow currants in that half a century timespan, we went through a generation or two and our cultural knowledge and memory of that fruit basically disappeared.

So now if you have grandparents of Eastern European descent, they probably know what black currants are, and if you showed them that you had some currants, they would be really excited. But beyond that, that cultural knowledge just really never got passed down. And so in this country we’re kind of fighting against that lack of memory, even though we have all the machines, the technologies, the recipes, everything to harvest and process and manage these plants really well because they’ve been doing it in Europe forever. We’re just kind of working to rebuild that cultural knowledge and awareness of this really great fruit.