This essay was recently published by staff member Bill Davison on his blog, Easy by Nature.

I reached out to municipal officials in my hometown in the fall of 2015 to propose that we work together to establish a food forest in a town park. I was inspired by the Beacon Hill Food Forest in Seattle, WA, and I wanted to create an edible urban forest where people could harvest berries, tree fruit, herbs, and nuts for free. Our primary goal was to create a public food forest where kids could explore and reconnect with food and nature. I was not sure how this idea would be received by town officials, so I entered into our first meeting with cautious optimism.

The city manager listened to the initial pitch, paused, leaned forward in his chair, and said, “If we are going to do this, we should do it right.” That set the tone for our project, and we were off to the races. The town offered up a prime 1.5-acre site within an existing park as a location for the food forest, and they requested a detailed plan and budget as the next step.

I partnered with graduate students in the University of Illinois agroecology program to develop a design and budget for the food forest. Two weeks later, I got my first look at a conceptual drawing, and it was love at first sight. A series of circular beds in a bull’s eye pattern radiated out across the site. Willows, chestnuts, hazelnuts, and a prairie formed the outside border and provided a sense of enclosure. The inner beds would contain small-statured plants like herbs, with raspberries, blackberries, and currants in the next few beds. Taller plants like fruit and nut trees would be in the outside beds.

We moved quickly at that point. The food forest became part of my job as a Local Food System Educator with the University of Illinois Extension, which contributed half of the funds for the initial planting and my time for managing the project. The town agreed to pay half the start-up costs and agreed to ongoing mowing and wood chip mulch delivery.

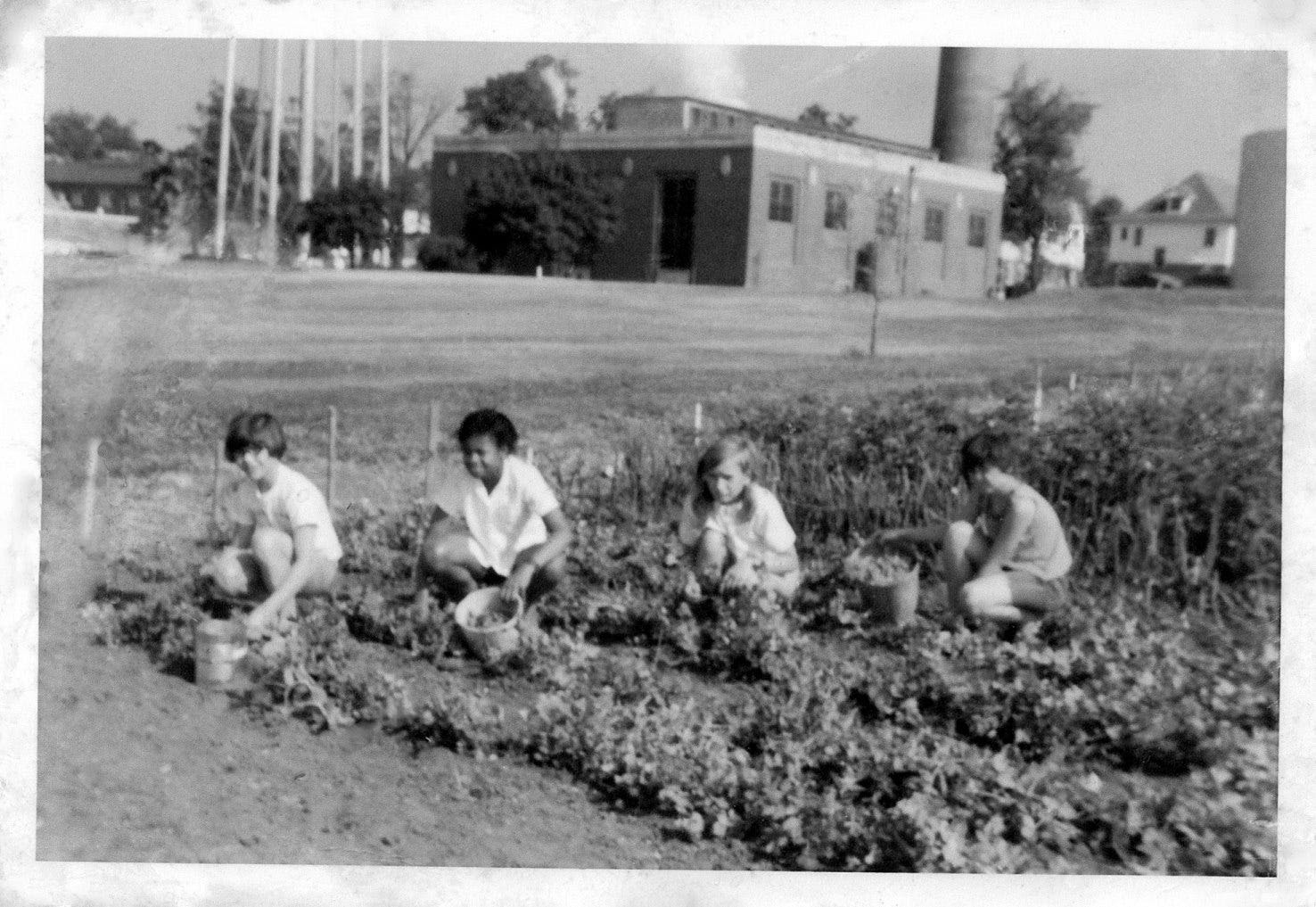

The next step was to lay out and till up the beds. The town’s park staff showed up with a small tractor and tiller and slowly tilled up the sod while following a maze of curving lines. I followed behind and inspected the beautiful silt loam soil. Signs of the past emerged from upturned roots. I found the heel of a boot, old rusty pieces of farm implements, buttons, and other clues to a past life for this land. This site was the location of the Illinois Soldier’s Orphans Home from 1865 through 1979. The soil we were tilling used to be part of a farm and vegetable garden tended by orphans. This land that served as a refuge in the past now offered the potential to be a refuge in the future.

Children at the Illinois Soldier’s Orphans Home picking peas in a garden that was planted where the Refuge Food Forest is now growing.

Seeing the beds marked out on the mowed grass made the project feel real. We started to get support from community groups and a sense that people were curious about our ideas.

On March 17, 2016, seventy-five volunteers joined us to plant the food forest. We planted 2,000 plants over the course of eight hours. The bare soil in the curving beds was now adorned with rows of bare brown sticks that appeared to be fragile and vulnerable. Time would prove otherwise.

The dormant plants settled in and explored new terrain. People found a sense of purpose and deep satisfaction in creating something that would live on past our lifetimes, weaving generations together with this natural touchstone.

Many relationships began that day as people connected with each other and the plants. Parents and kids worked together to carefully nestle plant roots into the soil. Tiny hands pressed the soil in place and straightened the bare stems. The stage was set for the miracle of photosynthesis to fuel new growth in the coming weeks.

The dormant plants quickly showed signs of life. Buds began to swell. Delicate bright green leaves unfurled. Roots explored the soil and connected with a vast fungal network, developing mutually beneficial relationships.

We prepared to support mutualism above and below ground by scheduling regular workdays over the summer and posting updates on the Refuge Food Forest Facebook page.

We knew the next couple of months would be critical to ensure the plants got off to a good start, so our workdays focused on what would become our primary activity: spreading mulch. We laid down landscape fabric and covered it with wood chips. Spreading woodchips became an annual ritual that the volunteers, soil, and plants appreciated.

When the plants started to produce berries in 2017, it was not uncommon to see kids running through the food forest with an adult trailing behind. In the summer of 2018, I watched a little kid run into the raspberries and say, “Come on grandpa, hurry up! I want to show you my favorite berries!”

Around this time, we started hosting berry-picking events for school kids. Most engaged in this activity with great enthusiasm; however, some kids approached a new berry with trepidation. I remember one little girl who picked a blackberry and held it out in front of her. She studied the shiny blackberry and attracted the attention of a few of her friends. They gathered around, curious about her reaction to this berry. She received conflicting advice. Some kids told her the berry tasted terrible; others said it was sweet. She popped the berry into her mouth. We all watched and waited. She began to chew, and a broad smile spread across her face. The other kids burst into laughter and ran off to eat more berries.

We had kids eating Black Currants by the handful. That was a revelation for me! When I saw kids relishing Black Currants, I knew the food forest would be a success. Black Currants are tart and astringent. Most adults will not eat them fresh, and they often advise their kids not to eat them. But, the appeal of berries to a young palate that is relatively free of social conditioning is so powerful it can overcome parental advice. The adults grimaced as purple juice ran down their kids’ chins.

Some of these kids became regular visitors to the food forest and connoisseurs of berries. They are poised to become well-informed consumers in the future, which could shape a healthier and more flavorful food system.

In the following years, the trees and shrubs grew quickly in the deep silt loam soil. We all enjoyed caring for the plants and watching them take shape. There were some setbacks from rabbits girdling stems, but 95% of the plants survived. We focused on feeding the life in the soil with wood chips. Four inches of wood chips would disappear into the soil in one season. All that life and energy fueled the plants.

The beds closest to our giant mulch piles ended up with thick layers of wood chips. You could see the different colors and textures of each year. The chips on the soil were fully colonized by white fungal mycelium, the next layer was intermediate, and the top layer was dark brown with more sharp angular pieces of wood in it.

As the trees grew and cast shade, they emanated a magnetic pull that drew people in like ants to a picnic. The “Winnie the Pooh” circle of poplar trees we planted shot up into the air with remarkable vigor and speed and created a leafy green enclosure. A picnic table took up residence in the center of the circle, and people started hanging out in the dappled shade amid the whispering leaves. A friend who is a counselor started meeting with clients within the circle. She told me that people always feel better after spending time with the trees.

Kids also explored the rapidly growing patch of young willows on the edge of the food forest. They weaved in and out of the limber green stems. Energetic youthful arms and legs intertwined with trees. Laughter filled the air, birds moved in, an oasis was born.